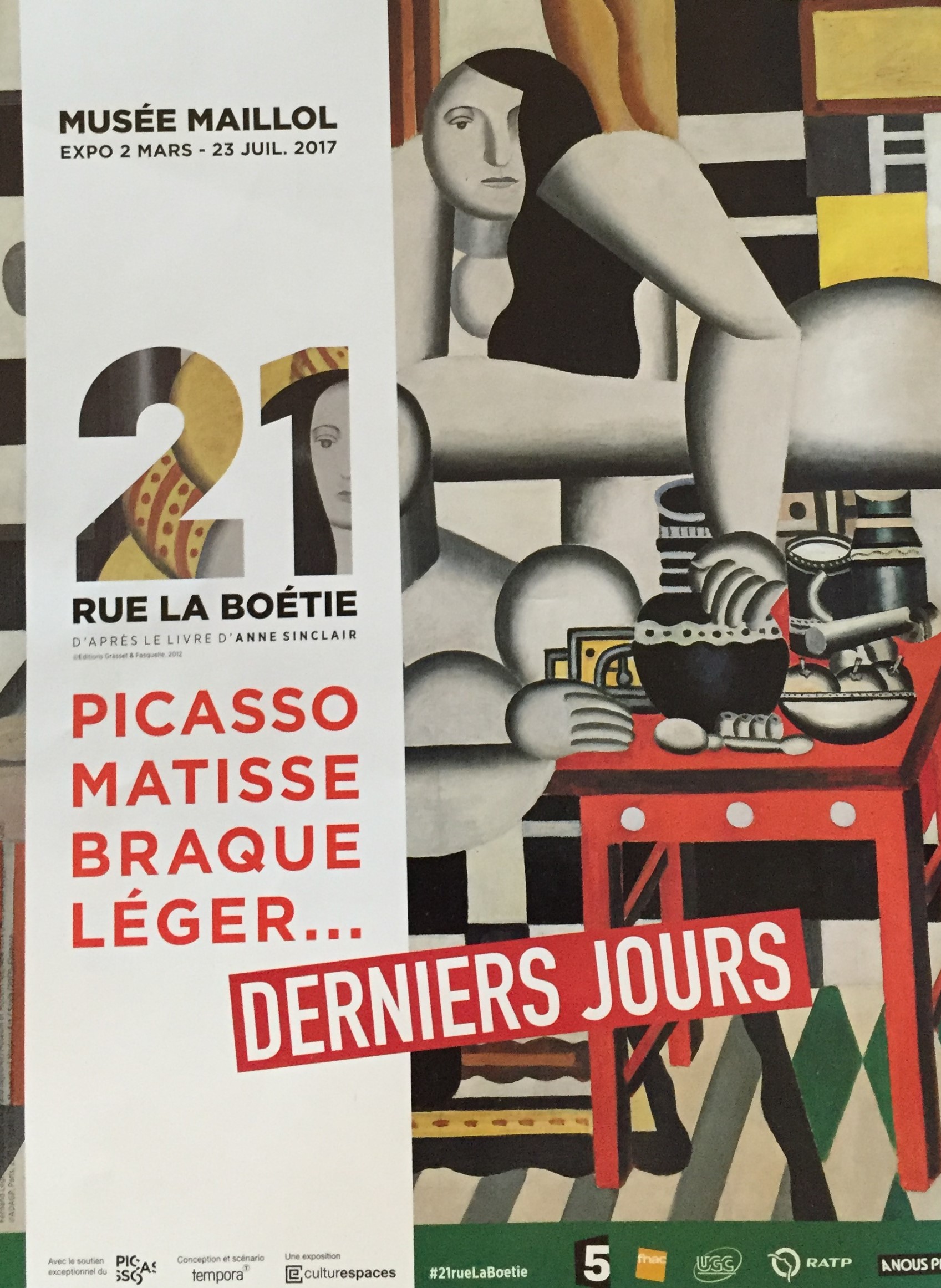

In July I was in Paris, in time for the last days of this exhibition, 21 rue la Boétie, at the Musée Maillol. I wanted to see the paintings as examples of modern art – I had no idea of the story behind this particular collection. On the very last day, 23 July 2017, a Sunday, I joined a small queue of people waiting patiently in a narrow street in the 7th Arrondisement, before the doors opened, our bags were searched and we were welcomed inside.

The exhibition brought together about 60 works of modern art (Picasso, Matisse, Léger, Laurencin…), many of which had transited through the Paris and New York galleries of Paul Rosenberg. Other paintings were ‘representative of the era’s historical and artistic context.’

However, the main emphasis of the exhibition was the story of 21 rue la Boétie in Paris. This was the gallery of art dealer Paul Rosenberg (1881-1959). The gallery opened in 1910 and Rosenberg promoted the work of Picasso and Georges Braque. Later, alongside the work of impressionists like Renoir, he exhibited paintings by Seurat, Monet and Matisse.

However, the main emphasis of the exhibition was the story of 21 rue la Boétie in Paris. This was the gallery of art dealer Paul Rosenberg (1881-1959). The gallery opened in 1910 and Rosenberg promoted the work of Picasso and Georges Braque. Later, alongside the work of impressionists like Renoir, he exhibited paintings by Seurat, Monet and Matisse.

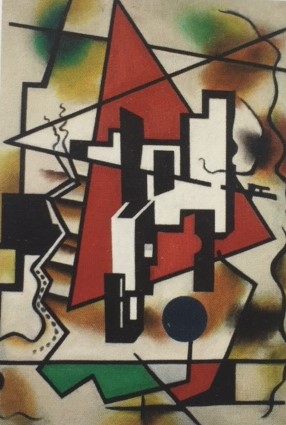

In 1940, the Nazis invaded Paris. Hitler had condemned modern artists like Picasso as ‘degenerate.’ In this context ‘degenerate’ meant works deemed to be ‘an insult to German feeling’. Rosenberg was a Jewish dealer in ‘degenerate’ art.

In one room where paintings from the Degenerate Art exhibition were displayed beside ‘Aryan’ paintings from Hitler’s art collection described by William Cook as ‘not entirely without merit, but all terribly samey.’ My own view was that they were simply boring – chubby faced children, meticulously transcribed horses, cheerful people, which lacked the energy and originality of the so-called degenerate art.

Rosenberg’s gallery was appropriated by the Gestapo as a centre for Anti-Semitic ‘research.’ Hundreds of his paintings, and as many as 20,000 other paintings were looted by the Nazis from national collections and private Jewish-owned art in France. They were placed in the Jeu de Paume gallery in Paris. Rose Valland, an art historian and member of the French Resistance, working in the Jeu de Paume, kept detailed lists of the paintings deposited there and where they were being transported, unbeknown to the Nazis.

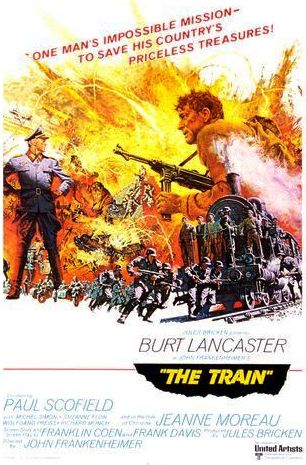

In 1944, with the Allies closing in on Paris, the Nazis packed the last hundreds of the paintings onto a train to Germany. However, this train was hijacked by the Free French Army, and the paintings saved. One of the soldiers who stormed the train was Rosenberg’s son, Alexandre. This incident was the inspiration for the 1964 film, The Train.

After the war, Paul Rosenberg – whose French citizenship had been removed by the Nazis and who became an American citizen – worked to reassemble his collection. About 400 paintings had gone missing. Eventually, over 300 were retrieved.

The exhibition was fascinating, both for the art and for the story of the Nazis’ involvement between 1941 and 1944.

So it seemed appropriate to watch the film, which also features Jeanne Moreau, who has so recently left us. It’s a great film, and even though you know how it ends, it’s gripping and heartbreaking and powerful. Burt Lancaster is a wonderful railwayman, all grease and passion, and Paul Scofield is excellent as the Nazi officer, cold, cruel and obsessed. They have changed the story somewhat but it’s a fascinating depiction of an intriguing piece of social history and well worth watching.